By Dylan Vernon, TIME COME #22, 6 June 2025.

There was no fanfare, no public ceremony, no crowd on 16th May 2025 when the ‘final’ report of the People’s Constitution Commission (PCC) was ‘presented’ to Prime Minister Briceño. This inconspicuous end was starkly different from the soaring and hope-filled rhetoric that greeted the large officious audience at the PCC launch in front of the National Assembly building two and a half years ago. After over 900 days and millions of the people’s money expended, there is growing evidence that a botched constitutional review process has resulted in a half-baked report so gravely flawed that it faces the prospect of an early burial. It appears that the PCC’s mandate was seriously bungled, and we are still very far away from a people’s constitution. What happened? How did we get here? Is there anything to salvage?

Low Expectations Justified

My deep disappointment in both the PCC journey and its product, makes it difficult to summon the usual mental energy to pen this TIME COME. Yet some readers have been asking for ‘my take’ and this is the purpose of my blog. In this first (or last) post on matters related to the now-disbanded PCC, I will focus on process issues and recent stakeholder reactions. I am yet to be convinced that dissecting the recommendations will be worth my good time or yours. However, I will share some general first impressions.

Before laying eyes on the penultimate ‘draft’ PCC report a few weeks ago, my expectations were already extremely low. (I am reliably informed that, apart from a new section that details the contrary or ignored views of some commission members, there were no substantive changes in the version the PM received compared to the draft — only minor corrections.)

My fears were, unfortunately, justified: a rare opportunity to decolonize our 1981 constitution has been bungled. Those who now contend that the PCC successfully completed its mandate on May 16, 2025 are spinning tales and/or delusional. Or maybe they have conveniently forgotten the PCC original mandate. So, let’s begin there.

Recalling the Mandate and the Promise

It’s critical to recall the PCC’s mandate because there are indications of attempts to edit both the original charge and the end game after the final whistle has blown. Most noticeable is the lame attempt to excuse the PCC failures, by ex post facto, sowing confusion on the PCC’s mandate — for example, to make it seem that the mandate was limited to the collecting, collating and then sharing of ‘data’.

The People’s Constitution Act, passed by the National Assembly in October 2022, charged the PCC with more than mere record keeping. It mandated the PCC to “draft and guide the process of promulgating a new Constitution for Belize or amendments to the Belize Constitution” based on widespread consultations with Belizeans at home and abroad.

The same National Assembly that enacted the PCC was to receive a final report from the PCC, through the Prime Minister, within 60 days after the eighteen months initially given to the PCC. The PCC ended up requesting and getting six-month extensions twice for a total of 30 months of legal life. Based on the amendment to the PCC Act passed by the House of Representatives on 12 May 2025, its members will not set hands on the report of the PCC until mid-2026, if at all. But time should be the least of our concerns.

Sure, the PCC Act could have given the PCC more independence and be clearer on the end game, and it is unfortunate that the PCC did not advocate for changes to the Act when it saw its limitations. But, however flawed in parts, the Act gave the PCC great latitude and political space to pursue its noble mandate. No part of the PCC Act limited how the PCC could design and conduct public education and consultations. And no part limited how the PCC could design its final report – as long as it reflected the concerns and desires of the Belizean people. Very importantly, if it so desired, the PCC could have included at least the skeleton of a new constitution in its report. It did not.

While the People’s United Party (PUP) government publicly committed to a referendum at the end of the process, Section 22 of the PCC Act states that the National Assembly must pass a “resolution declaring that the matter stated in the report … is of sufficient national importance” to be put to referendum. In other words, the Act itself did not mandate a referendum, and it is the PUP government, with its super majority, that will decide if there is one and what it is ‘the question’.

Botched Process

The impressions and concerns I shared on the PCC process in my TIME COME piece of 16 November 2024 were mostly on target, so I will not repeat everything here. The PCC itself promised that its process would include:

- Planning and orientation

- Public outreach and public education

- Public consultations

- PCC deliberations and drafting of recommendations

- Further public consultations on draft recommendations

- Finalisation of the report

- Presentation of the report

It is my considered view that the full record will show that the PCC did few of these phases well and, at least one, not at all. Every phase took more time than planned and most were plagued by unnecessary inefficiency and messiness. Even the planning phase was marred by confusion and misunderstanding of the PCC mandate among some commissioners. Perhaps nothing reflected this more than when the PCC sought early in 2023, and prior to any public consultations being done, to pre-determine, in effect, that a preambular clause should remain intact. By so doing, the PCC confused deciding ‘how’ it should do its work (planning) with ‘what’ should be reformed or not.

From what the PCC stated to the media, the all-important public education phase did not begin until June 2023 and ended in February 2024 or shortly after. Pending a full assessment, this is the only phase of the PCC process that I would rate as a C+. Even as the public education approach was more top-down lecturing to people, the informational documents produced by the PCC were useful and information on the Constitution was shared in country-wide sessions.

However, the public awareness numbers being touted by PCC need independent verification. For example, the draft report stated that there were 40,000 public responses. Is that really, really so? What exactly is meant by a public response? What are the categories? The former chairman recently stated that the PCC met directly with 22,447 people in 149 events and reached 18,536 students at 28 schools. So, were those 18,536 students a part of the 22,447 who were met directly? Then we are informed that ‘6,690 responses’ or ‘comments’ were received that had to be categorised and distilled to 167 recommendations. Lack of accuracy and rigour in the presentation of numbers tarnish both analysis and the credibility of conclusions.

From information available, the PCC gets a failing grade for public consultations and for the quality of its internal deliberations and decision-making. There was no clear distinction between public education and public consultation, resulting in public confusion as whether or not the PCC would ‘come back’ for consultations. Indeed, the PCC promised as much in its earlier sessions. It never really did. An interim report that was promised multiple times never appeared and the ‘draft’ that became the final report was never publicly shared. Broken promises are the remit of politicians not constitutional reform commissioners.

To top it all off, what the PCC did with the information and suggestions it received sounds like it was a recurring circus of poor execution of a flawed decision-making framework. But don’t take this from me. Take it from fish fram riva battam.

Fish fram riva battam

You may not believe this, but the ‘final’ version of the report, presented to the PM on 16 May 2025, was not shared (in hard nor e-copy) with all the PCC commissioners before the PCC disbanded. Nor was it signed by them – as is the norm with such high-level public commissions. The last meeting of the PCC on 14 May 2025 was virtual, yet its messiness was embarrassingly real.

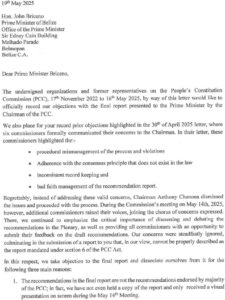

We get some of this information from a letter of May 19 2025 from eight of the 23 commissioners that were originally nominated by their organisations or sectors. Two alternates also signed the letter. The commissioners highlighted concerns about procedural mismanagement of the process, inconsistent record keeping, lack of robust analysis, the hijacking of decision-making by a sub-committee and “bad faith management” of the recommendations in the report. The signatories contend that the report lacked majority support, failed to uphold basic principles required by the Act and so “cannot be properly described as the report mandated under section 6 of the PCC Act.” Wow!

We get some of this information from a letter of May 19 2025 from eight of the 23 commissioners that were originally nominated by their organisations or sectors. Two alternates also signed the letter. The commissioners highlighted concerns about procedural mismanagement of the process, inconsistent record keeping, lack of robust analysis, the hijacking of decision-making by a sub-committee and “bad faith management” of the recommendations in the report. The signatories contend that the report lacked majority support, failed to uphold basic principles required by the Act and so “cannot be properly described as the report mandated under section 6 of the PCC Act.” Wow!

As a keen observer of the PCC process since the start, I am convinced that the damning concerns summarised in the 19 May letter are highly credible, even if the pulling of the public fire alarm about the ‘haligeta’ came late. Believe the fish! The PCC process began messy and ended even messier.

Some former commissioners or alternates have come out in public support of the final report. I count three so far and, of course, the former chairman. They have a very heavy lift but every right to rebut. They basically say that the decision-making process in the PCC was just fine and that all concerns were heard. How can commissioners on the very same commission have such divergent views on process matters?

The Honourable Henry Charles Usher, former minister of constitutional reform, has stated that the signatories did not understand their role. While he has a good point about the commissioners’ essential role being to receive the views of the people and translate these into a report, he is also glossing over how this was best to be done. The PCC mandate required doing more than just reporting ‘what the people are saying’. It was also to analyse all concerns, all input and translate into justifiable and holistic recommendations. Some of the inputs were bound to be in conflict with others. Sorting them out required serious deliberations in which competing philosophies of commissioners and their organisations were, realistically, bound to come out — for example, those of the commissioners representing the religious institutions, or those of the LGBTQ+ organisations). Furthermore, the PCC did not go back to the people for validation of findings.

If it were only a survey or poll of the people’s views that was required, the highly skilled Statistical Institute of Belize could have done it. The commissioners were not only “conduits”. They were, as the Act clearly states, “to conduct a comprehensive review of the Belize Constitution.”

If (at least) 35% of the former PCC commissioners have such grave concerns about the process, there had to be somethings that went seriously wrong. The situation is still dynamic, and it is good that Prime Minister Briceño has agreed to meet with the signatories of the May 19 letter. But what does this all mean for the disputed report.

Botched Product

If it is true that the final report in the hands of the prime minister is near identical to the version I have seen (apart from the collation of contrary views) many will be disappointed and some disillusioned. In format, that report reads like an incomplete and rushed high-school project. In substance, it lacks rigour of analysis, rational justifications of recommendations and holistic synergy.

Two and a half years and over two million dollars have been expended only to result in an uninspiring final product dominated by a messy mix of partially baked recommendations, some of which are so poorly introduced that they seem to just come out of thin air. The isolated nuggets of sense in a few recommendations (for example, becoming a republic, re-viewing the national symbols, broadening elections) cannot alone redeem the deep backwardness, disjointedness and contradictions of the whole.

I believe that the report will leave serious reviewers with the disillusionment that it is but a glorified working document on which the drafters gave up on mid-course. Like the unprepared student running out of time in the final exam, it appears that those who dominated the drafting threw in the kitchen sink and all without sufficient analysis and debate to support most recommendations. Did the PCC cut some corners because it lacked the organisational capacity required to conduct a substantive constitutional review and so failed at employing an effective and transparent consultative and decision-making process?

Very worrying is that the report’s recommendations have no overall philosophical coherence save being contaminated by the discriminatory overreach of the right-wing Christian church. It is clear that the commissioners representing these religious institutions on the PCC were highly organised and vocal in successfully advocating their positions. Were other commissioners unwilling, unable or not allowed to counter such religious fundamentalism? I say unable or not allowed because it is clear that some commissioners tried to call out the regressive proposals.

Should some of these recommendations (for example, discriminatory definitions of gender and of the family, and the constitutional enshrinement of the church-state educational system) ever make it to the Constitution, it would actually erode existing individual rights. We would be going backwards. Regressing!

You can see already why I question the usefulness of dissecting or rescuing this report. Some things in life are so broken it’s better not to touch them.

Government has the Ball

On 12 May 2024, four days before the PCC report was presented to the prime minister, the House of Representatives passed a bill to amend the PCC Act in one sitting. The effect was to extend the period of ‘executive review’ from 60 days to one year within which the PCC report must be passed on to the National Assembly. What odd timing!

The first parliamentary task of the Honourable Louis Zabaneh, in his new role as Minister of Constitutional Affairs, was an unpleasant one: to present and justify the PCC Act amendment bill. Every excuse possible was proffered: elections just happened, village council elections are coming, referendums are expensive, people have election fatigue, the report will take more time than anticipated to review. It was like throwing darts. But was it that someone in cabinet examined the PCC draft report and sounded the alarm that it was a hot but not fully baked potato? Some have speculated even worse: that the amendment is the shovel for burying the report.

As things stand, the government has the ball squarely in its political court. Not only does it have the responsibility, specified in the PCC Act, to present the PCC report to the National Assembly (now within one year), but the PCC, in handling over a flawed and now disputed report, gave the government the task of addressing the mess. Some in government may welcome this in that they now have even more leeway to cherry pick recommendations, to finish baking others to their taste and to include reforms not yet contemplated.

Witness, for example, that a new and controversial constitutional thirteenth amendment bill has already been presented to the House that seeks to further normalise the use of emergency powers (read suspending rights) by the state in combatting crime – a subject for a future post. There is no longer any inclination in government to wait for an examination of the PCC report by the National Assembly before doing constitutional changes.

It is clear to me that in bungling its mandate, the PCC has passed too much of the ball back to the very government who appointed it to deliver a new or revised constitution. The former PCC chairman had stated that the government should take the report back to the public. One former commissioner, in supporting the report, stated that some of the recommendations “need to be fleshed out.” This is risible given that this was exactly what the PCC had the mandate to do. Why share half-baked proposals? This is madness.

What’s the End Game Now?

So, now the prime minister says that the government will get a ‘specialist’ to assess the report. While the PCC Act requires that the report be presented to the National Assembly, there is, indeed, little lawmakers there can do with it in its current form. The report certainly can’t be put to referendum. And because the majority of these lawmakers are ministers or ministers of state (every member of the PUP in the House), what happens there will just be a formalisation of what the executive decides.

While I applaud the signatories to the 19 May letter, I am not sure what can happen after – even if the PM were to accept most of their concerns. They need to be clearer about their ‘asks’. Reconstituting the PCC to re-do the report makes no sense given what we know. What the PM should take away from that promised meeting with the signatories is that the disputed report before him is of limited usefulness – and say so to the public.

The government may be tempted to use the confusion around the PCC report to advance just the constitutional changes it wants or always wanted. Then a few reforms may be put to referendum and the government can proclaim that constitutional reform has been done – or at least attempted. By now you know that with a super majority in the House, the PUP does not even need a referendum to amend the constitution or to enact a new one.

What to do? It’s difficult to answer this given the mess. Some things are still dynamic. For sure, not only should the former commissioners of the PCC be immediately sent a copy of the disputed report, but the ‘final’ version should not remain hidden from the public — if it is supposed to reflect the public views. The prime minister should also inform the Belizean people what exactly the government proposes to do within this next year (a rescue plan) and how the people will be involved.

In the context of a flawed PCC process and report, what goes to the National Assembly cannot be just cherry-picked by the party in power. In lieu of a do over, which will be needed at some point, the people should have a say in what happens next.

Collective Blame?

What or who to blame? While there is some collective blame to go around, the PCC failed to successfully seize and use the political space provided by the PCC Act. The nation of Belize gave it this one rare responsibility. And it mucked it. The government now has a scapegoat to blame for not yet fulfilling its 2020 promises for meaningful constitutional reform.

This is not a matter of calling out individuals. But we must be brutally honest with ourselves. By passing back part of its mandate to the very government that mandated it, the PCC itself, in effect, admitted that it failed. Whether it be because of a botched process, poor leadership, an ineffective secretariat, confusing the role of alternates, lack of effort, some commissioners not understanding their role and/or inadequate analytical and writing skills, the PCC has failed in effectively “promulgating a new Constitution for Belize or amendments to the Belize Constitution.”

Or is it too that ‘we the people’ have, yet again, failed Belize? Is it that ‘we the people’ have dropped the ball? For now, the colonial system remains triumphant. Again. For now. In the meantime, workers of Belize unite!